'REFLECTIONS ON WAVEFRONT MAGAZINE'

by Al Razutis - 1998 - Updated as required

|

To access individual highlighted

articles or issues click on text-link; to view COVERS use picture-links.

|

WAVEFRONT magazine was conceived and created by me and Bernd Simson

in his holography studio in Vancouver-Burnaby, Canada; we started

the first issue on his small PC computer using "Wordstar"

for our desk-top publishing. This was 1985 and both personal computers

and software were in their infancy. WAVEFRONT's fundamental and guiding

purpose was to provide a forum for the many communities of holographers to

voice opinions, exchange views, and garner information.

Our editorial tasks went according to our interests: Bernd, a display and retail holographer, dedicated

himself to the corporate and commercial issues, whereas I focused on art and criticism.

These founding views are contained in our first editorial

"From the Editors" - (HTML file), in

Vol. 1, No. 1 - Summer 1985 (PDF file).

WAVEFRONT magazine was conceived and created by me and Bernd Simson

in his holography studio in Vancouver-Burnaby, Canada; we started

the first issue on his small PC computer using "Wordstar"

for our desk-top publishing. This was 1985 and both personal computers

and software were in their infancy. WAVEFRONT's fundamental and guiding

purpose was to provide a forum for the many communities of holographers to

voice opinions, exchange views, and garner information.

Our editorial tasks went according to our interests: Bernd, a display and retail holographer, dedicated

himself to the corporate and commercial issues, whereas I focused on art and criticism.

These founding views are contained in our first editorial

"From the Editors" - (HTML file), in

Vol. 1, No. 1 - Summer 1985 (PDF file).

One purpose behind >WAVEFRONT was to provide an alternative to HOLOSPHERE, the New York based publication which (at that time) typically offered technical tips, name-dropping press-release type information, and newsletter-type reviews of events and exhibitions - nothing contentious, risky, or investigative. We felt the holography community needed more in the form of investigative journalism and aesthetic debate and put a call out for contributors. Soon, we received a number of international responses, contributions, with interesting and varied points of view. I contributed two long essays in somewhat 'academic' style (I was a professor at the time) on "Art and Holography" - Part One, and the concluding, Part Two, are contained in our first two issues.

These early essays were written in somewhat formal style with the intent of laying groundwork for discussion on aesthetics and cultural analysis of holographic art. They included such 'rarified' ideas as semiotics, linguistic and cultural theory, and likely perplexed many of the holo-tech and business readers who were comfortable with press-release type info. These first essays were followed by a treatise on Avant-Garde for Holography by way of Nemesis, which involved (and cited) SURREALIST and DADA examples in an attempt to implicate holographic art practice within a the more general practice of 'fine art'. My culmination of this 'critical trajectory' was a unorthodox slide and academic presentation at a 80's SPIE conference (the 'display holography' section which I chaired) and featured a paper on Marcel Duchamp's The Bride Stripped Bare (By Her Bachelors, Even). This paper is in the SPIE archives or available here as PDF.

Though I might be somewhat biased (toward art and criticism), I believe the issues raised in these 1980's essays are still valid, if not more so, today. In the 80's and 90's criticism of holographic art styles and indulgences was scarce, aesthetic theories were largely non-existent, and pompous pronouncements about the 'future' or 'cosmic significance' of holography were in abundance. Today, as then, I see a lot of kitch, generic forms and ideas, imitations of earlier work and obsession with 'technique' standing in for content and cultural / historical context. The conceits of the 'lab guys' ('how big, how bright, how efficient is the hologram') were the talk of the time. And of course a number of artists fell for that 'easy way' of evaluating work. Resistance against criticism and aesthetic evaluations of content were the 'norm'. There have been but a few aesthetic theorists since (Andrew Pepper, Brigitte Burgmer) willing to take on 'holographic art' and not pander to the 'techies' for approval.

At WAVEFRONT, we did not set out to create controversy, but in an environment of professional etiquette (where no one will say what they 'really mean' except to leverage an art or business deal), and the conceits surrounding reputation and power, we found ourselves continually embroiled in it.

After the first several issues, Bernd Simson went on to other things, to manage his business; and the production team was joined by Carolyn McLuskie (a journalist) as managing editor, and Derrick Carter as graphics and layout designer. A lot of holo community snickering went on behind the scenes as we developed content, primarily from the technical and display holographers who were accustomed to in-house publications that focused on technology and had little use or understanding of the arts. But we were supported by intelligent contributors as well. We had a number of contributing editors who submitted writings from various locales, but in addition to Bernd, Carolyn McLuskie, and Derrick Carter, only Walter Clarke, Linda Law, Tulla Lightfoot, Ed Dietrich, and Melissa Crenshaw made regular contributions. But contributions from all concerned were appreciated. (Contributors-articles are listed in the various issues available on-line local page - links to articles. Technical support in setting up publication was provided by Jerry Barenholtz.

Our publication was feisty, combatative, and uncompromising. If you want confirmation of it, compare the various issues with their counter parts in Holosphere. Our directness and capacity to publish 'critical' articles tended to upset and offend some in the community. Some artists, who received unfavorable review of their work, harbored ill feelings long afterwards.

Certainly, the lack of critical dialogue between artist and curator, critic and the public was influenced by the enthusiasm and the novelty of this imaging medium in the 70's and 80's. Contexts (theories) of critical and aesthetic reference were difficult to come by and most established art institutions viewed holography as simply a technical curiosity. When shows, featuring the most trivial of subject matter were circulated, it did little to convince the 'art world' that this enterprise had something 'serious to say'. This was particularly true in the case of Hilton Kramer's (an established art critic of the Clement Greenberg school) famous broadside review in the New York Times (1975) which dismissed the first retrospective New York exhibition as being infantile and without "the slightest trace of esthetic intelligence." For ten years afterwards, I can't recall any assertive reply in print to Kramer's remarks and many of the shows in the 70's reflected the circus-like atmosphere (the "nursery" as Kramer called it).

'Biting the Hand that Feeds?

Due to our (Vancouver) geographical and institutional isolation, we didn't have to worry about 'playing the social game': there was no 'scene' or 'school' to protect, no museum to run, no theories to defend. We could be bold, and sometimes our boldness added to our difficulties. When we published an investigative article by Carolyn McLuskie on patents and infringements, titled "Patents Divide Holography Community" - (HTML) in a later issue (Vol. 2, No. 2 Spring 1987) (PDF file), this resulted in all kinds of corporate paranoia and suspicions (and of course, this affected advertising).

Critical viewpoints were risky in a young and immature market

The patents article was an extensively researched piece about

'the mess' of claims and counter-claims that had arisen in the numerous developments

based on the original inventions by Leith and Upatnieks. It was

dangerous stuff to even open this subject, since we relied on corporate advertising

to support our publication. People were capable of drawing the strangest

inferences. And even one of our prime advertisers, thinking that some

of the criticism was somehow directed at him, threatened to pull all ads. WAVEFRONT

tended to be a bit reckless (and most certainly 'cavalier') in its critical

intensity. There is a tough balance between positive criticism and negative

fallout. Whenever one mentions a particular name or work, the artist's

ego is predictably involved. In a climate of generalizations the act of

invoking particulars sometimes produces unpredictable results.

Critical viewpoints were welcome, appearing in Wavefront Magazine Vol. 1 No. 3

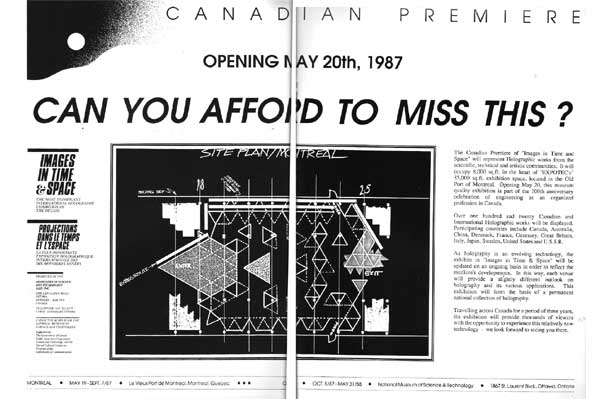

When we published an article on a exhibition at the Holos Gallery (San Francisco), titled "The Rise of Commercialism and Kitch " , criticizing the exhibited works of Cherry/Gorglione , it promted responses of outrage from this highly-established S.F. holo-couple. The fallout from this review continued for a decade. Closer to home, a negative review of a William Molteni retrospective exhibition at Interference Gallery in Toronto, "Historical Placements", Vol. 2, No. 2, - Spring 1987 - HTML , produced an angry outburst by the curator Michael Sowdon. When we published a informed review by pioneer Canadian holographer David Hlynsky, "Making Sense of Time and Space" - HTML , - in Vol. 2, No. 3 - Summer 1987 - (PDF file), criticizing aspects of the mega-exhibition "Images in Time and Space" we lost any potential for further AST (the governing body for the show) advertising and the planned co-production of a catalog for the show collapsed. When Michael Snow's EXPO '86 holography show was criticized, in a article titled "A Workmanlike Use of the Medium"( HTML) - in Vol. 2, No. 1 - Fall 1986 - (PDF file) , we lost the chance for a critically needed Canada Council grant to offset the huge financial burden that I personally bore as publisher. 'Playing the game' (i.e. being 'non controversial', but 'amenable') has always been the rule of 'social back scratching' in the commerce of the arts, and it has been anathema to any form of honest journalism.

After these difficulties, and unable to personally cover all the costs (as I had) any further, I was forced to stop publication.

IMAGES IN TIME AND SPACE center-fold full page ad

appearing in Wavefront Magazine Spring 1987

Some Things Just Improve With Age?

The magazine, in its brief years, had stimulated discussion, featured in depth research on issues, interviews, offended some, and perhaps we had a positive influence in invigorating a re-thinking of the arts and crafts of holography.

In the Special 'Holo-Recession Issue' - (Summer 1992) - (PDF file) (which was produced on 'no budget' and with the partial collaboration of Melissa Crenshaw< and others) we tackled the demise of the New York Museum of Holography and the "Images in Time and Space" show.

Response to our queries about the problems at the N.Y. Museum of Holography came back in the form of 'no comment' or a guarded (press release) statement from the Museum and Stephen Benton. With 'Images in Time and Space', the response was different. Deborah Dustin and others produced a wealth of information, Sunny Bains added editorial suggestions, and this input resulted in a well-researched article, "Lost In Time and Space" , that was highly critical of Dr. William McGowan's conduct with the administration and finances of the exhibition. It raised questions concerning the seemingly improper 'appropriation' by Dr. McGowan of a once-public and government-sponsored exhibition and corporate-donated collection. Dr. McGowan theatened to "sue for libel", yet none of the facts in the article were ever disputed (in any court of law or public forum), nor were the circumstances concerning fiscal irresponsibility ever corrected.

There have been no further issues beyond the 1992 Special Issue (PDF file), and no futher articles except the ones published on this site.

Many of the problems the magazine raised have come back to haunt the holographic 'scene'; opportunist players have moved on to greener (digital) fields. Scandals have been swept under 'the carpet' of polite discourse. The art of holography is still misunderstood, at times ridiculed by a general public that has only seen mass-produced shit, kitch, and bad installations. The Images in Time and Space exhibition is 'somewhere' (parts in South America, parts in storage, parts lost forever.) Holographers are becoming less courageous as the poverty cycle affects them more and more at middle age. The infrastructure of much of holography, that is not tied to 'security' embossed holograms and embossed wallpaper, has collapsed. And a lot of the original entrepeneurs have moved on to 'digital domains' presumably mining new medias 'for what they are worth.'

In Retrospect

In retrospect, one thing is certain: WAVEFRONT produced not only a difference in how holography as art and technology was understood, it produced a series of informative, courageous, and historical articles. Importantly, it featured a number of fascinating interviews with pioneering holographers: Rudie Berkhout, Michael Sowdon, Anait Stephens, Sally Weber, and Margaret Benyon.

The magazine's coverage included New York as well as Los Angeles scenes, and the publication (and writers) received a number of congratulations, and awards to Derrick Carter for its 'patents in ice' cover (left).

During the magazine's existence, support came from art, science, and industry sectors, in the form of advertising and contributions. It also received anonymous donations (thank you Posy Jackson, Anait, and others...!), letters of congratulations..... and a lament when it disappeared from the scene.

Al Razutis, Los Angeles, 1996-98

-- With appreciation to URS FRIES (Holonet) for first collecting and re-publishing various texts of WAVEFRONT in 1996. HOLONET

PAGE WITH LINKS OF AVAILABLE ARTICLES

WAVEFONT 2000 - On-Line - FINAL ISSUE:

[VISUAL ALCHEMY HOME] [WEST-COAST ARTISTS IN LIGHT]

[TOP OF PAGE]